CT scanning (see the images below) is useful for demonstrating the morphologic evidence of cirrhosis within the liver and in showing mesenteric and GI tract abnormalities, as well as the development of collateral vessels in portal hypertension.

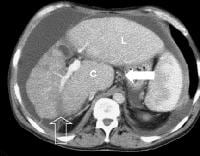

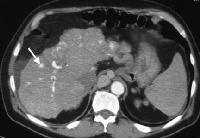

Patient with cirrhosis showing tortuous hepatic arteries in addition to enlarged left lobe and caudate (C)

Patient with cirrhosis showing tortuous hepatic arteries in addition to enlarged left lobe and caudate (C) More advanced cirrhosis. Computed tomography (CT) scan with a portal venous–phase image shows a markedly enlarged left lobe (L) and caudate (C), with an area of focal fibrosis and atrophy of the posterior right lobe, deforming contour (open arrow). Incidental note of prominent collaterals in lesser curvature region (white arrow)

More advanced cirrhosis. Computed tomography (CT) scan with a portal venous–phase image shows a markedly enlarged left lobe (L) and caudate (C), with an area of focal fibrosis and atrophy of the posterior right lobe, deforming contour (open arrow). Incidental note of prominent collaterals in lesser curvature region (white arrow) Computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrates irregularity of the external contour of the left lobe.

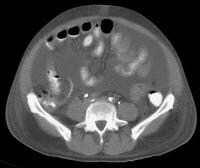

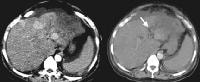

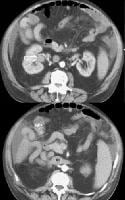

Computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrates irregularity of the external contour of the left lobe. Secondary manifestations of cirrhosis include thickening and edema of the small and large bowel, as well as of the gallbladder wall, which is more common in the setting of ascites and hypoproteinemia. A thickened small bowel is demonstrated here in a 51-year-old patient who has cirrhosis with marked ascites.

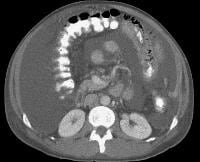

Secondary manifestations of cirrhosis include thickening and edema of the small and large bowel, as well as of the gallbladder wall, which is more common in the setting of ascites and hypoproteinemia. A thickened small bowel is demonstrated here in a 51-year-old patient who has cirrhosis with marked ascites. Computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating edema of the colon in a patient with cirrhosis. Note the presence of marked ascites.

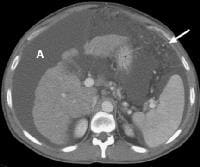

Computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating edema of the colon in a patient with cirrhosis. Note the presence of marked ascites. Portal venous–phase computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating a thickened gallbladder wall, splenomegaly, numerous collaterals within the omentum (arrow), and marked ascites (A). The liver is atrophic and irregular in its external contour.

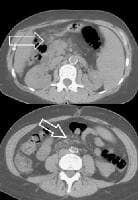

Portal venous–phase computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating a thickened gallbladder wall, splenomegaly, numerous collaterals within the omentum (arrow), and marked ascites (A). The liver is atrophic and irregular in its external contour. Extrahepatic manifestation of cirrhosis. Mesenteric edema and stranding is identified (open arrow). (Note marked splenomegaly.) Same patient: A computed tomography (CT) scan at more inferior level, the root of the mesentery, shows infiltration around the superior mesenteric vein and artery (arrow).

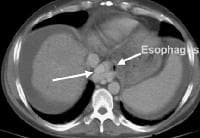

Extrahepatic manifestation of cirrhosis. Mesenteric edema and stranding is identified (open arrow). (Note marked splenomegaly.) Same patient: A computed tomography (CT) scan at more inferior level, the root of the mesentery, shows infiltration around the superior mesenteric vein and artery (arrow). Development of extensive collateral vessels at the lower esophagus, short gastric vessels places this 42-year-old patient with cirrhosis and portal hypertension at risk for a GI hemorrhage. Note ascites and marked splenomegaly.

Development of extensive collateral vessels at the lower esophagus, short gastric vessels places this 42-year-old patient with cirrhosis and portal hypertension at risk for a GI hemorrhage. Note ascites and marked splenomegaly. Same patient as in the previous image, section more cranial. Varices are adjacent to and within the esophageal wall.

Same patient as in the previous image, section more cranial. Varices are adjacent to and within the esophageal wall. A patent, collateral paraumbilical vein (arrow) arising in the ligamentum teres is an indication of the early development of portal hypertension in a 56-year-old female patient with cirrhosis. This can be traced to the umbilicus and its anastomosis with systemic, superficial abdominal wall vessels in image below.

A patent, collateral paraumbilical vein (arrow) arising in the ligamentum teres is an indication of the early development of portal hypertension in a 56-year-old female patient with cirrhosis. This can be traced to the umbilicus and its anastomosis with systemic, superficial abdominal wall vessels in image below. Portal venous–phase computed tomography (CT) scan. Note the superficial vessel (arrow) anastomosing with the paraumbilical vessel (same patient as in the previous image).

Portal venous–phase computed tomography (CT) scan. Note the superficial vessel (arrow) anastomosing with the paraumbilical vessel (same patient as in the previous image). In this computed tomography (CT) scan of a patient with long-standing cirrhosis, the arterial-phase image is indicated by enhancement of the aorta and hepatic arteries (enlarged, tortuous right hepatic artery [RHA], arrow). The intrahepatic left portal vein also is opacified (arrow), as are numerous enlarged paraumbilical collaterals. Simultaneous enhancement of arterial and portal structures on the early arterial-phase images indicates the presence of a large arterioportal venous shunt. Marked splenomegaly is present. Note also the prominent superficial veins in the abdominal wall.

In this computed tomography (CT) scan of a patient with long-standing cirrhosis, the arterial-phase image is indicated by enhancement of the aorta and hepatic arteries (enlarged, tortuous right hepatic artery [RHA], arrow). The intrahepatic left portal vein also is opacified (arrow), as are numerous enlarged paraumbilical collaterals. Simultaneous enhancement of arterial and portal structures on the early arterial-phase images indicates the presence of a large arterioportal venous shunt. Marked splenomegaly is present. Note also the prominent superficial veins in the abdominal wall. Same patient as in the previous image, section more caudal. The image shows a very large varix in the umbilical region (clinically evident as a caput medusa).

Same patient as in the previous image, section more caudal. The image shows a very large varix in the umbilical region (clinically evident as a caput medusa). Splenorenal shunt. Collateral vessels are identified medial to splenic hilum and anterior to upper pole left kidney (arrow). Note gallstones, which are frequently present in patients with cirrhosis.

Splenorenal shunt. Collateral vessels are identified medial to splenic hilum and anterior to upper pole left kidney (arrow). Note gallstones, which are frequently present in patients with cirrhosis. Splenorenal shunt. A collateral vessel passes caudally (arrow) and enters the left renal vein (open arrow) (same patient as in the previous image).

Splenorenal shunt. A collateral vessel passes caudally (arrow) and enters the left renal vein (open arrow) (same patient as in the previous image). A more advanced example of a spontaneous splenorenal shunt, in a patient with alcohol-related cirrhosis. Upper figure: A large, dilated collateral vessel is present anterior to spleen (arrow). Lower figure: Collateral vessels contiguous with the perisplenic collateral vessel (arrow) feed into the left renal vein (open arrow).

A more advanced example of a spontaneous splenorenal shunt, in a patient with alcohol-related cirrhosis. Upper figure: A large, dilated collateral vessel is present anterior to spleen (arrow). Lower figure: Collateral vessels contiguous with the perisplenic collateral vessel (arrow) feed into the left renal vein (open arrow).Splenomegaly and the presence of ascites, depicted in the second image above, are readily determined.

CT scanning is commonly used to evaluate acutely decompensated patients with suspected subacute bacterial peritonitis, in order to exclude other inflammatory causes. CT scanning is valuable in characterizing lesions shown by US techniques or in evaluating decompensated patients with cirrhosis. In addition, it is increasingly being incorporated into the management of stable patients undergoing screening to identify neoplastic lesions.

Delineating lesions

With improved technology, which permits rapid dynamic scanning using helical or multi-slice CT scanners, scanning of the liver in multiple phases of contrast enhancement is now routinely recommended as the most sensitive method of detecting space-occupying lesions and evaluating vascular structures. However, substantial limitations remain in delineating small lesions (< 2 cm), particularly in patients with advanced cirrhosis.

Characteristic form of HCCA

The most characteristic form of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCCA) is a hyperattenuating nodule noted on arterial-phase imaging, with hyperattenuation and/or hypoattenuation developing on portal venous–phase imaging, shown below. On CT scanning, hyperattenuation in the arterial phase occurs in a variable proportion of cases, and in many instances, it is characteristic enough to permit confident diagnosis.

Arterial-phase computed tomography (CT) scan shows focal fatty sparing adjacent to the gallbladder fossa (arrow), which mimics a small hepatocellular carcinoma. This abnormality became less visible on a subsequent CT-scan evaluation as the overall level of fatty infiltration decreased.

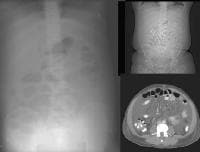

Arterial-phase computed tomography (CT) scan shows focal fatty sparing adjacent to the gallbladder fossa (arrow), which mimics a small hepatocellular carcinoma. This abnormality became less visible on a subsequent CT-scan evaluation as the overall level of fatty infiltration decreased. A 51-year-old male who has cirrhosis with massive ascites. On kidney, ureters, bladder (KUB), and digital scout view, small bowel loops are seen primarily in the midabdomen. The abdomen appears hazy. A computed tomography (CT)–scan axial view confirms the presence of small bowel loops floating centrally in ascitic fluid and of the existence of fluid in paracolic gutters.

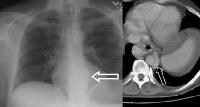

A 51-year-old male who has cirrhosis with massive ascites. On kidney, ureters, bladder (KUB), and digital scout view, small bowel loops are seen primarily in the midabdomen. The abdomen appears hazy. A computed tomography (CT)–scan axial view confirms the presence of small bowel loops floating centrally in ascitic fluid and of the existence of fluid in paracolic gutters. An abnormal soft-tissue density is seen (arrow) in the lower mediastinum, superimposed over the shadow of the descending aorta. This density represents massively dilated esophageal varices on the corresponding computed tomography (CT) scan (arrow), just above the level of the left hemidiaphragm, immediately adjacent to the aorta.

An abnormal soft-tissue density is seen (arrow) in the lower mediastinum, superimposed over the shadow of the descending aorta. This density represents massively dilated esophageal varices on the corresponding computed tomography (CT) scan (arrow), just above the level of the left hemidiaphragm, immediately adjacent to the aorta. Varices at the gastroesophageal junction (arrow), demonstrated on an upper GI series. The varices become more prominently seen on Valsalva maneuver. A computed tomography (CT) scan in the same patient shows enhancing collateral vessels.

Varices at the gastroesophageal junction (arrow), demonstrated on an upper GI series. The varices become more prominently seen on Valsalva maneuver. A computed tomography (CT) scan in the same patient shows enhancing collateral vessels. Characteristic unifocal hepatocellular carcinoma in male alcoholic with cirrhosis. Precontrast scan shows 4.7-cm hypo-attenuating lesion in the left lobe of the liver.

Characteristic unifocal hepatocellular carcinoma in male alcoholic with cirrhosis. Precontrast scan shows 4.7-cm hypo-attenuating lesion in the left lobe of the liver. Arterial-phase computed tomography (CT) scan (same patient as in the previous image). Increased attenuation in the lesion is demonstrated.

Arterial-phase computed tomography (CT) scan (same patient as in the previous image). Increased attenuation in the lesion is demonstrated. Portal venous–phase computed tomography (CT) scan. The hepatic parenchymal enhancement is increased and the lesion has mixed hyperattenuated and hypo-attenuated regions, with a central area of hypo-attenuation.

Portal venous–phase computed tomography (CT) scan. The hepatic parenchymal enhancement is increased and the lesion has mixed hyperattenuated and hypo-attenuated regions, with a central area of hypo-attenuation.Attenuation

Nino-Murcia and colleagues described arterial enhancement with abnormal internal vessels or a variegated appearance.[21] In some instances, a single hyperattenuating focus may be the only evidence of HCCA, with no distinguishing characteristics on precontrast or portal venous-phase images. However, a proportion of lesions are hypo- or iso-attenuating on arterial-phase imaging. Dysplastic nodules also may be very similar to HCCA in their enhancement characteristics, shown below.

Regenerative nodules in patient with cirrhosis. Evanescent multiple subcentimeter hyper-attenuating lesions on arterial-phase imaging. It is difficult to distinguish these nodules from malignant lesions. The nodules represent a continuous spectrum of response to hepatic injury, with increasing levels of dysplasia culminating in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Regenerative nodules in patient with cirrhosis. Evanescent multiple subcentimeter hyper-attenuating lesions on arterial-phase imaging. It is difficult to distinguish these nodules from malignant lesions. The nodules represent a continuous spectrum of response to hepatic injury, with increasing levels of dysplasia culminating in hepatocellular carcinoma.However, hypoattenuating nodules depicted on a CT scan have high malignant potential. In the series by Takayasu and coauthors, 36 (60%) of 60 such lesions converted to hyperattenuating lesions, with the cumulative attenuation conversion rates of these 60 lesions reaching 58.7% within 3 years of follow-up.[22] Thirteen of the lesions were biopsied immediately after attenuation conversion was observed to prove that they were HCCA. The presence of hepatitis C viral antibody and lesion size at detection were correlated with the attenuation conversion rate.

Documenting complications

CT scanning is useful in documenting complications associated with HCCA, such as portal vein thrombosis, and can be used to identify malignant invasion with a high specificity, as portrayed in the image below.

Vascularized thrombus (arrow) enhancing within the main portal vein on an arterial-phase computed tomography (CT) scan. A multifocal tumor is in the right lobe of the liver (M).

Vascularized thrombus (arrow) enhancing within the main portal vein on an arterial-phase computed tomography (CT) scan. A multifocal tumor is in the right lobe of the liver (M).The images below depict multifocal HCCA, which is commonly associated with extensive portal vein thrombosis and/or invasion at the time of diagnosis. Often, extensive portovenous shunts are present.

Advanced multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma. A tumor nodule is in the right lobe, and there is an enlarged inferior vena cava with enhancement in the arterial phase (arrow), indicating malignant invasion

Advanced multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma. A tumor nodule is in the right lobe, and there is an enlarged inferior vena cava with enhancement in the arterial phase (arrow), indicating malignant invasion Same patient as in the previous image. Arterial-phase computed tomography (CT) scan shows tumor hyperattenuation and mass with hyperattenuation within the inferior vena cava.

Same patient as in the previous image. Arterial-phase computed tomography (CT) scan shows tumor hyperattenuation and mass with hyperattenuation within the inferior vena cava. Multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma (same patient as in the previous 2 images). Note the prominent venous collaterals secondary to the inferior vena cava obstruction in the subcutaneous tissues.

Multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma (same patient as in the previous 2 images). Note the prominent venous collaterals secondary to the inferior vena cava obstruction in the subcutaneous tissues. Arterial-phase and portal venous–phase computed tomography (CT) scans show multifocal lesions of hepatocellular carcinoma in the liver and demonstrate no opacification of the left portal vein from the thrombus (arrow). Minimal right portal opacification in the portal venous–phase image is seen. The patient presented with hematuria.

Arterial-phase and portal venous–phase computed tomography (CT) scans show multifocal lesions of hepatocellular carcinoma in the liver and demonstrate no opacification of the left portal vein from the thrombus (arrow). Minimal right portal opacification in the portal venous–phase image is seen. The patient presented with hematuria. Portal venous–phase computed tomography (CT) scan (same patient as in the previous image) shows collateral vessels. Enlarged portions of the right renal vein also are demonstrated (open arrow) and drain into the distended inferior vena cava (*).

Portal venous–phase computed tomography (CT) scan (same patient as in the previous image) shows collateral vessels. Enlarged portions of the right renal vein also are demonstrated (open arrow) and drain into the distended inferior vena cava (*).Degree of confidence

The enlargement of the caudate lobe in cirrhosis, with other regions of retraction, is depicted in the image below and may be mimicked in patients with breast carcinoma metastatic to the liver who are undergoing chemotherapy. Young and colleagues suggest that the mechanism is through nodular regeneration.[23]

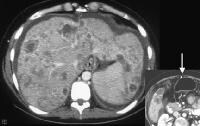

Breast carcinoma can mimic cirrhosis, with enlargement of the left lobe, irregularity of the surface contour, and development of portal hypertension (see patent paraumbilical vein on insert).

Breast carcinoma can mimic cirrhosis, with enlargement of the left lobe, irregularity of the surface contour, and development of portal hypertension (see patent paraumbilical vein on insert).Outcome

Concerns regarding the evaluation of patients with cirrhosis and HCCA for transplant are related to the likelihood of a successful outcome based on the stage of the carcinoma; solitary HCCAs that are smaller than 2 cm can be treated successfully with transplantation. Survival rates diminish with the presence of additional or larger lesions, with a 5-year survival rate of only 75% reported by Mazzaferro and coauthors for patients with up to 3 discrete lesions that are smaller than 3 cm or with solitary lesions of 2-5 cm.[24]

Transplantation

Transplantation is of no benefit when the lesions are diffuse or multiple, because metastatic disease is usually present. The discovery of a lesion or multiple lesions in a patient with cirrhosis who is otherwise well compensated necessitates further imaging evaluation or biopsy to characterize the lesions accurately. This assists in deciding whether to refer the patient for transplant or other therapy.

Multiple abnormalities

Often, multiple abnormalities are present in 1 patient, including a spectrum of nodules in various stages of malignant transformation. One or more frank HCCAs may coexist with several dysplastic nodules and/or a multiplicity of regenerative nodules, making the likelihood of accurate pretransplant diagnosis minimal without highly refined imaging techniques.

In patients with advanced cirrhosis, peak enhancement of the liver is reduced and enhancement may appear heterogeneous, reducing the level of detection of focal lesions.

Distinguishing nodules from HCCA

Much effort has been devoted to distinguishing regenerative nodules from dysplastic ones, and dysplastic nodules from HCCA. CT scanning techniques, such as CT arterial portography ([CTAP], in which the liver is visualized following a superior mesenteric artery [SMA] injection in the portal phase) and CT arteriography (which utilizes direct injection into individual hepatic arteries, with imaging performed in the arterial phase), have been extensively investigated. Matsui and coauthors asserted that most low-grade dysplastic nodules have almost the same histopathologic and hemodynamic characteristics as those of regenerative nodules; therefore, they are iso-attenuating to regenerative nodules at CT scanning and are not usually visualized on CT arterial portography.

High-grade dysplastic nodules may have a decreased portal supply and an increased arterial supply, but Lim and colleagues found the presence of such changes to be extremely variable; the grade of nodular dysplasia does not seem to affect the presence of the portal and arterial supplies.[25]Differentiating dysplastic nodules from HCCA is a difficult task because some low-grade dysplastic nodules lose the portal supply and gain an arterial supply, while some high-grade dysplastic nodules retain the portal supply without gaining an increased hepatic arterial supply.

Monzawa and colleagues reported that small HCCAs may be detected more accurately by combining the characteristics of arterial-phase, portal venous–phase, and delayed-phase images.[26] A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis for combination 3-phase imaging was significantly higher than for arterial-phase and portal venous–phase imaging (Az = 0.940 vs 0.917).

In patients with advanced cirrhosis, a sensitivity of 88% for CT scanning in the detection of HCCA was obtained by Chalasani and coauthors, compared with 62% for AFP measurement and 59% for US.[14] However, the accuracy of 3-phase dynamic CT scanning in detecting tumors in cirrhotic livers smaller than 2 cm in diameter is in the range of 60%, with a somewhat higher accuracy for lesions of 2-5 cm (82%), based on a study by Lim and colleagues of 41 patients whose livers were explanted before transplantation.[27] This was corroborated by a study by Peterson and colleagues of 77 North American patients undergoing liver transplantation.[10]A prospective sensitivity of 59% for the presence of HCCA and a sensitivity per lesion of 37% were found.

A subsequent study of 88 patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation, evaluated pre-operatively with multidetector CT (MDCT) scanning by Ronzoni and coauthors, confirms that despite improved detector technology and scan speed, no real improvement in sensitivity can be expected from MDCT.[28]Observers detected 89 of 139 hepatocellular carcinomas in the 88 patients, with a sensitivity of 64%. However, the specificity was only 75% because many regenerative or dysplastic nodules were present, leading the authors to caution against overestimation of disease that might preclude patients from liver transplantation.

Characterizing nonmalignant lesions

CT scanning is useful in the characterization of nonmalignant lesions, such as hemangiomata, which occur with relatively high frequency in patients with cirrhosis. Other, more invasive forms of CT scanning have been evaluated over the past few years; Jang and colleagues reported evidence that CTAP and CT hepatic arteriography add little or no additional information to that obtained using triple-phase, helical CT scanning in the detection of HCCA.[29]

False positives/negatives

Dysplastic nodules may mimic HCCA. Nontumorous arterioportal shunt in livers with cirrhosis has been reported by Kim and colleagues as mimicking hypervascular tumor.[30]

A higher injection rate may increase the number of small, false-positive, hypervascular lesions. Ichikawa and coauthors studied 60 patients with suspected HCCA; they reported in 2006 that the use of an iodinated contrast injection rate of 5 mL/sec resulted in an 18% reduction in specificity, from 67% to 48%, with no significant change in sensitivity (88% vs 80%) compared with a 3 mL/sec injection rate.[31]

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar